First, wealthy individuals can purchase water to drink.

In Congo, people’s perception of water purifiers may not be adequate. Their demand for water purifiers was not particularly high due to the low national income. In shopping malls or on the streets, one could not see any shops selling water purifiers. I asked some locals where their drinking water source was, and they replied that affluent individuals all bought bottled water to drink.

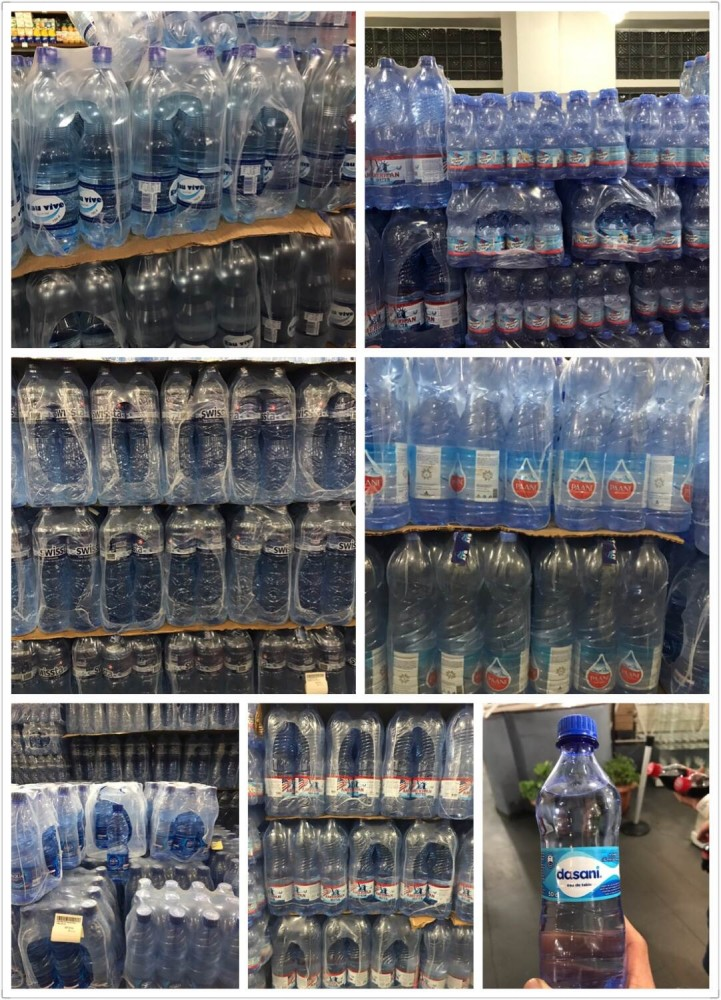

Secondly, the market for bottled water.

In Kinshasa, there were 28 different brands of bottled water. Coca-Cola’s bottled water brand is called Dasani here, along with other brands such as Canadian Pure, Swissta, and American Water, among others.

If you would like to know about the water quality analysis in Kinshasa, Congo, please download this; it is free: https://www.easywellwater.com/tw/knowledge/marketing/5/136

Thirdly, there are rich mineral deposits in Congo. Congo’s copper mines have the second highest yield in the world. There are abundant deposits in this region, including gold, diamonds, and cobalt.

According to local bottled water manufacturers, people living in the suburbs obtain water from wells. Even bottled water is produced from underground water.

Due to the rich mineral deposits in the area, the heavy metal content of the underground water is very high. Local residents are at risk of heavy metal poisoning, so we need to be cautious about this.

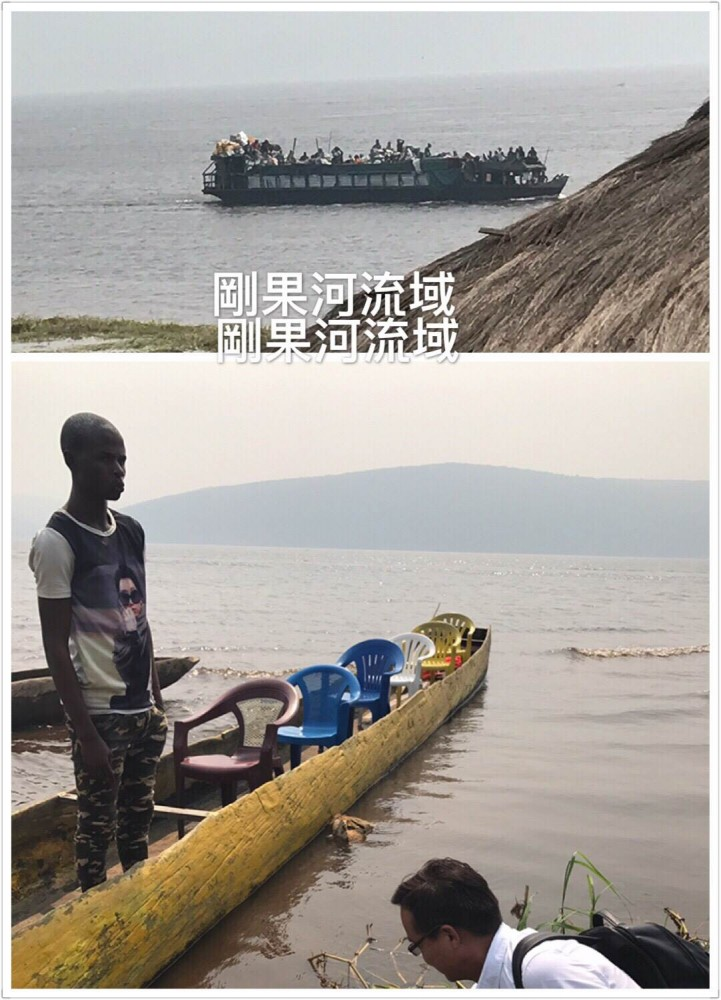

Fourthly, the Congo River. The Congo River is the second largest river in the world. It is 4,640 kilometres long and is also the deepest river in the world, with an average depth of about 200 metres. Furthermore, it is unmatched in terms of its streamflow and hazards.

In Congo, the Congo River flows rapidly, enabling the development of hydroelectric power, which accounts for 90% of total electricity generation. However, the machinery at the power plants is quite old, resulting in frequent power outages. When I was waiting for my flight in Kinshasa, I encountered one of these outages.

Fifth, the national income in Congo.

In Congo, the average wage for blue-collar workers is between US$100 and US$150 a month, while white-collar salaries are about US$200 a month. (This information was provided by Mr Yang, who was the chairman of the bakery.) However, police officers earn only US$50, which has led to significant corruption. Most of our members were asked for bribes when we entered Customs. I even paid US$20 to leave Congo.

Sixth, the poorer the country, the dirtier the banknotes tend to be.

I have been to Nigeria, where every banknote was old and dirty, and the same is true here.

Seventh, one of the most dangerous countries in Africa.

According to information from Wikipedia, the Congo is one of the most dangerous countries in Africa. Supermarkets are required to hire a policeman to stand at the door with a gun. In Kinshasa, even Mr Yang, who runs a bread factory, had to hire six armed policemen to provide 24-hour security. When the Taiwanese supervisors went out, they had to have bodyguards with them.

The receptionist asked me twice if I needed a bodyguard when I wanted to go out for dinner or to the supermarket. It’s similar to the situation in the Philippines and Nigeria. This country is not only dangerous, but corruption within Customs is also a significant issue. Even getting through Customs presents obstacles; how can this country be respected and make progress?

Lastly, the traffic in Kinshasa.

I had travelled to Africa many times for business, but I had never seen a traffic jam like this. The traffic jam situation in Kinshasa was more serious than that in Cairo. On a six-lane road, cars were driving on the wrong side simply because of the congestion. Vehicles from the opposite side even drove onto our road and occupied two of our lanes.

According to the local driver, the people who lived here were Catholic. They went to church at 4:30 p.m. on Sunday, and when we arrived, they had just finished.

After two days (it was Tuesday), I went to the airport to catch my flight. I was apprehensive about the traffic, so I set off six hours earlier than scheduled. Although it wasn’t Sunday, there were still a lot of cars on the road. I noticed that the six-lane road had no traffic lights; it was no wonder it always experienced congestion. I heard that Boulevard Lumumba was built by the Japanese. I wonder if the Japanese architects were aware of this situation—what would they feel?